The south of England used to be known for aircraft manufacturing. Just think Brooklands/ Vickers, Kingston/Hawker, Hatfield/de Havilland, Radlett/Handley Page, Luton/Percival, Reading/Miles, Shoreham/Beagle, Christchurch/ Airspeed, Brockworth /Gloster, Yeovil/Westland and the subject of this story, Filton/Bristol. All bar Westland are no longer with us. All the factories and in most cases the airfields have been consigned to history. But what a history that was! Britain was home to the leading lights in aircraft design and manufacturing, none more so than the company that was to become the Bristol Aeroplane Company at Filton airfield near Bristol.

Filton airfield has now been closed for several years and has succumbed to new roads, warehouses and houses. But the famous Brabazon hangars have survived and there are plans afoot to use them as part of a new entertainment complex with exhibition halls and conference facilities. Some of the old 1900s Belfast-truss hangars have become the Aerospace Bristol museum along with a custom- built hangar for G-BOAF, the last Concorde to fly. There is still some aerospace activity on the airfield with Airbus continuing to have a large presence along with Rolls Royce. However now the Air Ambulance has moved to a new home there is no longer any flying at the site.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s go back to the beginning of this famous partnership between Bristol aircraft and Filton. The Bristol Tramway and Carriage Company Limited was founded by William Butler, its first Chairman. He was an associate of George White who in 1875 came to work for the tram company as part-time company secretary. Over the years White’s involvement grew and by 1887 he had become Managing Director. Following the death of William Butler in 1900, George White (later Sir George White ) became Chairman of the Bristol Tramways and Carriage Company. Having met Wilbur Wright and seen the Wright Flyer, George White decided to get into the aircraft manufacturing business.

With his son and brother he founded the Bristol and Colonial Aeroplane Company Limited in 1910. Despite the full name of the company most of its planes were simply referred to as being built by Bristol. The new company’s first premises were a pair of tram sheds leased from the Bristol Tramway Company. A small flying field was set up alongside at Filton. Looking around for a design to build the company went to France and did a deal with famous aircraft designer Gabriel Voisin to use one of his designs as the basis for the first Bristol-built machine. This design was a failure and didn’t even fly so George White got his money back from Voisin and decided to use a Henri Farman design instead.

Drawings for the new aeroplane were produced in just one week. Known as the Boxkite, the first of 76 examples had its maiden flight on 20 July1910. Many of the first examples went to the Bristol and Colonial flying schools that had been established at Brooklands and Larkhill. Aircraft were also sold to governments both at home and abroad.

At the outbreak of the First World War it was obvious that the Boxkite was not suitable for any further development and the company started to look into new designs. One of these was the Scout bi-plane which was built for the RNAS (Royal Naval Air Service) as a reconnaissance aircraft but was later developed into the first single seat fighter to be used by the British forces. The type’s life at the forefront of fighter design was short-lived, becoming obsolete by 1916. However 374 of these little fighters were produced and used not just by the RNAS but the RFC (Royal Flying Corps) and the Australian Flying Corps as well. Here in the UK one was rebuilt a few years ago from just a handful of original parts that had been handed down through a family who then decided to rebuilt Grandad’s aeroplane. It can be seen flying on the air show circuit today.

With the Scout having been usurped by more modern machines, in 1916 Bristol presented its new Bristol Fighter F2 to the military. Originally designed as a reconnaissance aircraft it quickly became clear that the new aeroplane had the speed and makings of a fighter. An order was placed and the first offensive action using six of the new machines took place in April 1917. It was a disaster. Four of the six were shot down and a fifth badly damaged. Learning from this, improvements were made to both the aeroplane and the tactics used and the Bristol Fighter or ‘Brisfit’ as it was known, became a potent fighting machine. 5329 were produced and used by many air arms including the Polish Air Force who ordered 106 in 1920. Indeed, the aircraft was so useful, the RAF kept its last Bristol Fighter until 1932.

Later in the war Bristol was to introduce the Bristol M1C, the only British built monoplane to see service during the conflict. 130 of these well-liked planes were built. In 1920 the board of the Bristol and Colonial Aeroplane Company Limited decided to formally have their aeroplanes known just as Bristol, so the company was renamed the Bristol Aeroplane Company Limited. It was also at this time that the company branched out into the aero engine business buying up Cosmos engines. In 1927 the Bristol Bulldog fighter took to the sky for the first time. The RAF liked what they saw and placed an order, the first of which entered service in 1929. A total of 443 examples were built with many being exported overseas. The RAF flew the type until 1937. Just two survive, one in Finland and one at the RAF museum at Hendon. This particular aircraft was the company demonstrator and was flown well into the 1960s until a major crash at the 1964 Farnborough air show ended its flying days. The damaged remains sat in store for many years before the RAF museum restored it to static display condition and placed it on display at Hendon.

By 1934 the Bristol Aeroplane Company works at Filton was the largest aircraft manufacturing plant in the world. The interwar years saw the company produce one of its more iconic designs when in 1935 the Bristol Type 142 first flew from Filton. Built as the personal transport for press baron Lord Rothermere its immense speed for the time brought it to the attention of the RAF. This civilian aeroplane was faster than all of their front-line fighters with a top speed of 307mph. An order for a bomber version was placed and the new aeroplane was to be called the Blenheim. The bomber saw heavy action during the first few years of the Second World War but fighter development soon saw its speed advantage disappear and the Blenheim became very vulnerable during daylight raids. A night fighter version was produced and this was more successful. A total of 4422 of all types were built in the UK and other countries such as Canada who called them the Bolingbroke, with a number being exported to such countries as Greece, South Africa and Finland who took 58 in 1935.

Another iconic Second World War type built at the Filton site was the Bristol Beaufighter. First flying in 1939 almost 6000 were built and the last RAF example was retired in 1960. The Beaufighter was built as a heavy fighter, ground attack aircraft, torpedo bomber or a night fighter. A truly multi- role aircraft like its contemporary the Mosquito. From the start of the project it only took eight months work before the prototype had its first flight. This was achieved by using many parts from the earlier Beaufort design. Most of the Beaufighters were powered by the Bristol Engine division Hercules radial engine, others with the iconic Rolls Royce Merlin. Production was also undertaken in Australia with 364 examples being produced down under. Beaufighters were used not just by the RAF and RAAF but examples also operated by New Zealand, USA, Canada and many other countries. After the war Portugal, Turkey and the Dominican Republic also operated the type. Such was the demand for the aeroplane a satellite factory was set up at Weston-Super-Mare and an abandoned quarry near Corsham Wiltshire was converted into an underground factory for the production of the Hercules engines. Sadly there are no airworthy Beaufighters left today although for several decades the Fighter Collection at Duxford have been working to bring an ex-RAAF example back to the skies. For whatever reason the project has stalled but the mainly complete airframe can be seen in their hangar, let’s hope one day she will take to the skies again.

Towards the end of the war development work had started on a new cargo plane capable of carrying a three-ton army truck. The design was to be known as the Bristol Freighter and its first flight took place in December 1945. As the war had now ended military interest waned but a civilian version, known as the Wayfarer was produced to carry passengers. There was limited interest from abroad for the military Freighter but commercial airlines who bought most of the 214 examples that had been completed when production ended in 1958. The very last Bristol Freighter was bought new from the factory by Dan-Air. Many of the civilian Freighters went on to set up the famous cross channel car ferry service with the likes of Silver City and Channel Air Bridge flying regular services to France. The very last Freighter flight was in 2002 when the final airworthy example flew to a museum in Alberta Canada. For many years there were no Freighters in Europe, but this was rectified in 2018 when an ex-New Zealand Air Force machine which had been in store for 40 years was shipped back for eventual restoration and display at the AeroSpace Bristol Museum. At the time of writing this aeroplane is still sitting dismantled in storage at Filton.

Way back in 1937 the Bristol company began looking into building a very large long-range bomber powered by eight engines operating in pairs. The design did not attract any attention from the UK military so it was shelved, dusted off in again in 1942 and again shelved when the Ministry decided to go with the Lancaster rather than a new long-range bomber. After the 1942 publication of the Brabazon committee report into future UK civil aircraft requirements Bristol decided to revamp its bomber design into a civilian airliner and bingo! An order for two prototypes was received from the government.

The new airliner was named the Brabazon, capable of carrying 100 people in absolute luxury across the Atlantic. The cabin was to feature sleeping berths, lounges and even a 37-seat cinema. The huge aeroplane would be around the size of a modern day Boeing 767 and was the first aeroplane to have full powered flying controls, electric ‘fly by wire’ engine controls and a high pressure hydraulic system. So big was the new plane it was quite apparent that the facilities at Filton would need massive reconstriction. This included building a large assembly shed capable of holding eight Brabazons, a 6000 feet extension to the runway which was also widened to 300 feet and the demolition of a village. On 4 September 1949 the giant lifted off the runway for the first time, powered by eight Centaurus piston engines. It was planned that the second prototype would be powered by the new Bristol Proteus turbprop engine. The future however was bleak as BOAC was no longer interested in the aeroplane as the time of super luxury for a few passengers had passed. Despite everybody’s best efforts the British government cancelled the project in 1953 and the prototype and partially completed second aircraft were broken up for scrap.

With things not looking good for the Brabazon, Bristol had started work on a new design for a four- turboprop engine transatlantic airliner called the Britannia. This was to meet another of the Brabazon committee requirements for a medium-range airliner. The ministry had given Bristol an order for four prototypes back in 1949 but it was not until 1952 that the prototype first flew. The aeroplane made its public debut at the 1952 Farnborough air show where people commented on how quiet the large airliner was. It was later given the nickname ‘The Whispering Giant’. Problems with the Bristol-built Proteus led to delays in starting production and the loss of the second prototype which crash-landed on the Severn River mud flats due to an engine fire did not help progress. Engine icing problems were also an issue. This could have easily been resolved but BOAC made a big thing of it and the subsequent mods and tests delayed the Britannia’s entry into airline service by two years and by that time the early jets had arrived massively damaging any sales prospects of the turboprop Britannia. 86 would be built with many going to the RAF. Even with the massive floor area of the Brabazon hangars Bristol could not cope with the order from the military so they sub- contracted Shorts of Belfast to build the RAF aeroplanes.

The Bristol Aeroplane Company did not just make aeroplanes and aero engines but over the post- war years branched out into helicopters, cars, buses, missiles and even fibreglass composite boats. Their core business was of course the planes and in 1962 the first of three stainless steel research aircraft took to the sky. Known as the Bristol Type 188, work had started in 1953 to build the planes as research aircraft for a potential Mach 3 bomber. One aircraft was intended for ground use and the other two would be flying test beds for new materials for the proposed bomber. This high speed bomber project was felled by the defence review axe in 1957 and cancelled. However the Bristol 188s continued to be built as research aircraft to look into thermal heat soak of new materials for use on future high speed aircraft. The pair of aircraft flew for just two years as they did not carry enough fuel to fly for long enough to test the heat soak into their skins, their whole raison d’etre! Knowledge that was gained was very useful in the next Bristol project a supersonic airliner.

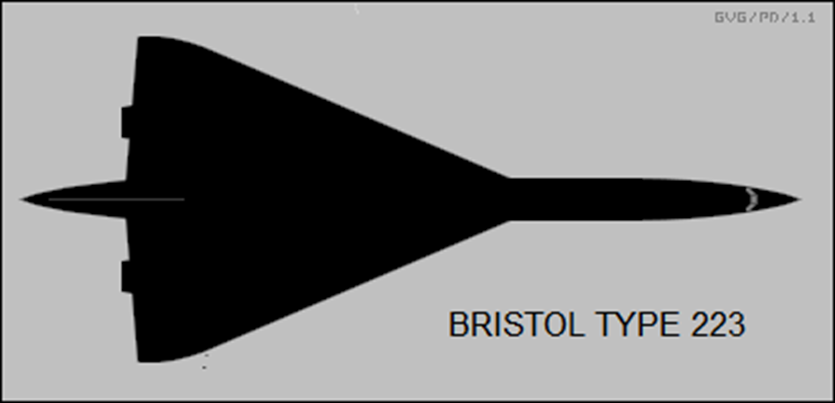

In the late 1950s Bristol had begun studies into a supersonic airliner to be known as the Bristol 223. This aeroplane would be built of traditional Duralumin after the problems encountered with the stainless steel of the Bristol 188. It would fly around Mach 2.2 powered by four Bristol Engine Division-made Olympus jets. Before much more detailed work could be done, in 1960 Bristol was forced by government policy to merge with a number of other aircraft companies to form BAC (British Aircraft Corporation) and it was they who took the project further. In 1966 the Bristol engine division was taken over by Rolls Royce. Both BAC and Rolls Royce continued to use the old Bristol facilities at Filton. BAC entered into talks with Sud Aviation of France who were also developing a supersonic airliner with a view to a joint project to cover the huge costs such an undertaking would incur. The rest, as they say, is history with the Bristol 223 layout being used as the basis for the new airliner which would become Concorde.

In April 1969 the first British prototype flew from Filton having been assembled in the huge Brabazon hangars. It took another seven years of testing before Concorde entered service with British Airways and Air France. Just 20 examples of this elegant delta were produced split equally between Toulouse in France and Filton here in the UK. The type would remain in service for the next 27 years before in November 2003 G-BOAF, made the very last Concorde flight back to its birthplace at Filton to be preserved as an example of the ground-breaking engineering that had come out of the Bristol/BAC factory since 1910. After many years sitting out in the open, in 2017 BOAF entered a purpose built hangar where she is now open for the public to view as part of the Aerospace Bristol Museum.

From 1977-2002 British Aerospace (which was formed by the merger of BAC and Hawker Siddeley) used Filton for the manufacture of various components for their BAe146 feederliner. With BAe being part of the Airbus group they also made components for those aircraft, mainly wing parts. BAe also converted Airbus A300 airliners into freighters and ex-civilian VC10s into aerial refuelling tankers for the RAF. In 2002 BAE Systems (formed by the merger of BAe and Marconi) decided to quit all work on civilian airliners and in 2012 it closed Filton as an airfield and moved out leaving Airbus as the major user of the site with a new wing development and manufacturing plant being built in 2016.

If you visit Aerospace Bristol, the skies above Filton will be silent. But look across what is left of this once proud aviation complex and you can easily imagine the ghosts of the past taking flight.

‘till the next time Keith

Registered Charity No. 285809