For many years the Daily Mail had been the leading newspaper when it came to offering prizes for imaginative air races. This started in 1909 with a prize of £1,000 (£52,000 in today’s money) for the first person to cross the English Channel in an aeroplane, it was won by Louis Bleriot.

Fifty years later in 1959, the paper sponsored another air race to commemorate that first historic crossing. This time the route was from Marble Arch, London to the Arc de Triomphe Paris. The total prize money for this event was £10,000 (£190,000 today). The race was won by an Englishman, RAF Squadron Leader Charles Maughan who used a motorbike and Sycamore helicopter to get to Biggin Hill airfield. Here he jumped into his Hawker Hunter and flew to Villacoublay airfield, a helicopter to Issy heliport just outside Paris and finally a motorbike to the Arc de Triomphe arriving 40 minutes 44 seconds after he had left Marble Arch, winning the £5,000 (£95,000) first prize.

In 1969 ten years after the Paris race the paper decided to celebrate another 50th aviation anniversary: the non-stop crossing of the Atlantic by Alcock and Brown in 1919. The challenge was simple, a race across the Atlantic from London to New York or more accurately the top of the GPO (later BT) Tower in London to the top of the Empire State building in New York. The race ‘window’ would be eight days in May. Competitors could make as many entries as they liked in either direction. The total prize money offered was £60,000 (£840,000 today). The entry fee was just £10 (£140) per crossing and the prize money was to be split over many different classes to give everybody a chance. When the race started in May there were 397 entries, some were non-starters but at the end of the eight days of racing there had been 345 crossings of the Atlantic.

In May 1969, with Concorde having taken to the sky only two months earlier, it was a foregone conclusion that the overall winning time would come from the military, hence there were separate classes for military and civilian entries. The Daily Mail went to great lengths to get a good response from the military worldwide so that there would be a keen competitive spirit between teams. The RAF were keen to show off their new Harrier VTOL jet but found official approval was difficult to obtain. The Royal Navy who in 1969 had a potential winner in their F4 Phantom supersonic jets would not commit themselves. The newspaper cast its eyes across the Atlantic with hope the US military would take up the challenge. It was apparent the USAF and USN would have loved to enter but the US Department of Defence blocked any involvement citing the ongoing war in Vietnam as a reason. With the Alcock and Brown flight having originated from St John’s Newfoundland it was gratifying for the organisers that an entry did come in from the Canadian Air Force who planned to fly the route with a helicopter, landing on frigates in the Atlantic to refuel! Once again the top brass stepped in and killed the entry stone dead. Thus it fell to just the RAF, Royal Navy and the British Army to fight for the service honours.

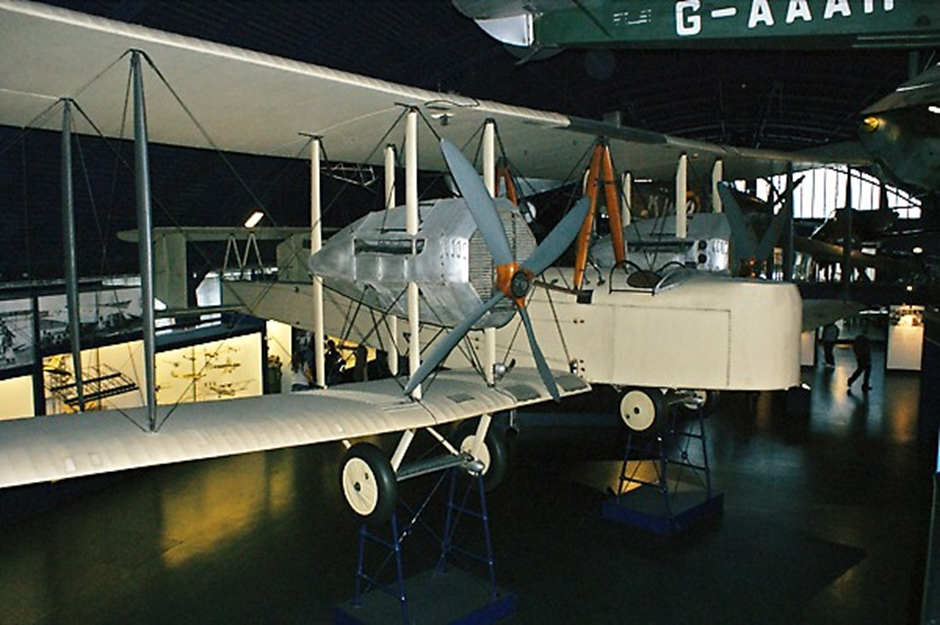

Wishing to commemorate Alcock and Brown in a very appropriate way was a group intending to fly across the Atlantic using a Vickers Vimy replica they were having built. The same type of plane used by the pair in 1919. Sadly it wasn’t finished in time but did go on to fly and now has a resting place at the Brooklands museum.

The RAF eventually got official permission to use their new Harrier jump jet and announced plans to make attempts in each direction using the revolutionary jet. They also obtained permission to use a disused coal yard at St Pancras station as the take-off base in London and permission to land on the United Nations pier on New York’s East river. All the teams knew that the race would be won or lost by the time it took to get from the starting points to their aircraft. To this end the UK services had been in secret talks with developers, who had a large site adjacent to the GPO tower, for use of a corner of their land to build a temporary helipad. This meant the service personnel would be able to run direct from the GPO tower to their helicopter for the onward flight to their fast jets.

The Royal Navy finally showed their hand and it came as no surprise they intended using their supersonic Phantom jets with three entries all competing on the New York-London route. This was to make use of the prevailing winds as a jet the size of a Phantom could not land in the centre of town like the Harrier and they needed to get as much time in the bag as possible to remain competitive against the Harrier. The Phantoms would have the use of a USN base near New York and would arrive in the UK at Wisley airfield Surrey where a Wessex helicopter would rush the competitor to the temporary helipad alongside the GPO tower. The Navy had also obtained the help of the RAF and their Victor tankers, as the Phantoms would need refuelling three times during their Atlantic dash. HMS Nubian was positioned in the Atlantic to use its radar to guide the Phantoms onto the tankers.

With the need to use their Victors to refuel not just the Navy Phantoms but also their own Harriers the RAF decided on four attempts at the subsonic prize, two in each direction using Victors. RAF VC10s also made attempts at a prize, one carrying Prince Michael of Kent who had entered the race as a competitor. The service contestants would be in a race of their own with the bulk of the other race entries being civilian. These again were broken down into several categories, fastest charter flight, fastest flight using a scheduled airline, fastest flight routing via Shannon (sponsored not unsurprisingly by Aer Lingus), business jet, light aircraft, most meritorious non-winner etc. The civil classes attracted much more interest from the USA with many private flyers wanting to fly their own planes across the Atlantic in the spirit of Alcock and Brown. One such entrant was Ben Garcia and his small Piper Colt. Even with extra fuel tanks fitted it was a fact of life that the aeroplane would run out of fuel on the Iceland to Ireland leg. His answer to this was to glide the last 99 miles! In fact the small Piper would only have stayed aloft for about 20 miles It was fortunate that he crash landed in the US on his way to the start line! Determined not to waste his entry he then proceeded to make several runs across the Atlantic in various fancy dress outfits using scheduled airlines!

Also starting in New York was Canadian Neil Stevens who intended flying his Tiger Moth across to London. Neil lived in Vancouver and unfortunately the Tiger had a mishap on its way across Canada to New York and broke its propeller. With no spares at the scene of the accident it was decided to put the plane on a truck and ship it across to New York where a new prop could be fitted. The gods were not smiling on the Tiger as a huge storm further damaged it en-route and it was unable to be repaired in time for the race. Undeterred Neil packed the broken prop in his bag and took a scheduled flight to Prestwick where a British Tiger Moth was waiting for him to complete his journey to the GPO tower. This effort saw him walk away with the Brooke-Bond tea award of £2000. It was not just from the USA that characters were emerging. One of the entrants from London, 18 year-old Rosemary Stanford Smith stamped her time card at the top of the GPO tower and was then immediately parcelled up in a plastic bag by specialist freight company McGregor Swain before being unwrapped on a table at the top of the Empire State building almost 8 ½ hours later. Record-breaking pilot Shelia Scott had entered her beloved Piper Comanche in the race and took the opportunity to break four more transatlantic records on the way to New York winning the female-light aircraft class in a time of just over 26 ½ hours. This netted prize money of £1000 from the Evening News.

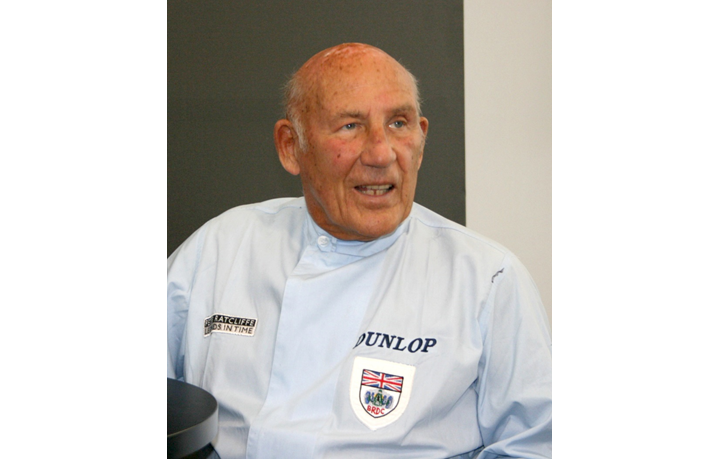

Another female making the trip from London to New York was Tina, one of the Brooke Bond Tea chimps! Having punched her own time card at the GPO tower she was driven by Rolls Royce to Heathrow to board the BOAC VC10. Here her VIP status took a bit of a knock as she had to travel in a crate, but on arriving at New York it was back to her expected luxury when a limo whisked her to the Empire State building for a time of just under 10 hours. There were many celebrities taking part such as Clement Freud, Mary Rand, Stirling Moss and Sir Billy Butlin to name but a few. A very special celebrity was the first contestant away from London, Anne Alcock, the niece of John Alcock. Her crossing, like her uncle’s, did not go very smoothly after she misplaced her passport and missed the helicopter link to the Empire State building from Kennedy airport. Many of the competitors used scheduled airlines for their crossings along with a huge variation of routes from the start lines to the airport. Wanting to keep his ground time as low as possible Stirling Moss first jumped on a high- powered motorbike for a dash to the Thames where a waiting launch took him out to a barge being used as a helipad in the middle of the river. A helicopter flew him to Gatwick touching down directly on the tarmac adjacent to a waiting BUA VC10 for the trip across to New York where another helicopter/bike combo would deposit him at the steps of the Empire State Building.

With no Concorde yet in service the VC10 was on paper the fastest airliner across the Atlantic so these flights were of particular interest to the competitors. However a TWA Boeing 707 Captain was not going to let the VC10s have an easy run and he discovered that if he flew at around 27,000 feet instead of the usual 35,000 feet it would cost him more fuel but the aeroplane would be faster as the engines developed more power in the thicker air. The BUA VC10 with Stirling Moss on board set a good time but it was beaten by a BOAC VC10 chartered by businessman Tony Drewery. He had filled his chartered jet with 139 businessmen from all walks of life who would use the trip as a sales tour to the USA. The entire group were all dressed in pinstripe suits and bowler hats each carrying a brief case and umbrella! Their arrival at New York created a great stir and the trip was an unprecedented success with many millions of pounds worth of trade being done by the group. With the help of helicopters, motorbikes and a New York ambulance they beat the Moss attempt by four minutes and their time was fast enough to take the prize for fastest time by a chartered business jet.

Other entrants, realising they had no chance of a major prize, were just taking part for the sheer fun of it. Some endeavoured to see just how slowly they could make the crossing, another did the run from New York to London with a hood over his head to prove he could navigate his way by ESP! For ground transportation, motorbikes, cars, a rickshaw a Roman chariot and even hot air balloons came into play. Much of the motorised transport paid little regard to the speed limits in London and it has to be said the police in most instances turned a blind eye. Only one airline was officially interested in entering the race and that was the US airline Capitol International. They eventually provided a DC-8 to fly from Stansted with 54 passengers. All entered the race under the Capitol banner. Despite the lack official interest, every airline that carried an entrant on their scheduled flights bent over backwards to help ‘their competitor’. Airport formalities were waived, staff led the running contestant through the airport and airliners often sat on the ramp engines running just waiting for the air race competitor to jump on board. With many airline slots very close to one another once the planes had started taxiing there was much jostling for a prime take-off or landing slot at the other end.

The big interest in the race was however the military teams as it would be these who would take the top overall spots. On day one both the RAF with a Victor flying to New York and the Royal Navy with a Phantom flying from New York posted their first times. As the first hectic day came to an end both of these crews were sitting in the top spot for their chosen direction.

The next day was the one the public had been waiting for: the first Harrier flight from London to New York. As Squadron Leader Tom Lecky-Thompson burst out of the ground floor doors of the GPO tower his RAF Wessex was already just lifting off at the adjacent helipad. Helping hands pulled the Squadron Leader into the cabin and the big helicopter set off for St Pancras station coal yard. Before the wheels had touched down the Harrier pilot was racing for his machine sitting on an aluminium pad in the middle of the disused yard. As the Pegasus engine wound up, the dust started to rise and as the Harrier did the same the whole area disappeared under a black cloud of coal dust as the little jet streaked away for its first hook-up with a Victor tanker. On arriving at the United Nations pier on the East river in New York the Harrier touched down and Lecky-Thompson raced to a waiting Jaguar car which sped him the rest of the way to the Empire State Building punching his time card at 6 hours 11 minutes 57 seconds beating the previous day’s Victor crew by just under five minutes. His time would hold for the rest of the race and the Harrier was the fastest service aircraft on the London to New York route of the race. The Royal Navy already held top spot for the New York-London route with their run on the first day. They made two more attempts using Phantoms over the next few days with the final effort taking place on the last day of the race when they knocked almost nine minutes off their original time posting a race winning 5 hours 11 minutes 23 seconds.

For those eight days in May 1969 the public had been transfixed by the events unfolding in the air race. Every night the BBC and ITV had updates and stories, papers and other TV channels around the world featured the event. It was estimated that the Daily Mail achieved in 1969 prices £3,000,000 of free publicity. There had been 345 attempts to cross the Atlantic and only one entrant failed to complete the course. Whichever way you looked at it the event had been a huge success and a very appropriate way to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Alcock and Brown’s first non-stop crossing of the Atlantic.

Could something like this happen again? Sad to say, most probably not. Several 100th anniversaries came and went and with newspapers no longer being the money making machines they once were it’s difficult to see a paper coming up with the required sponsorship. Also, can you imagine the Health and Safety brigade letting people get away with flying helicopters off barges mid-Thames and jumping in and out of them whilst airborne? And high-powered motorbikes paying scant regard to speed limits let alone environmental groups having a pink fit as the sky around St Pancras turned black with coal dust !

But for those of us who saw it, in the flesh or on TV there will always be fond memories of a great event and a jolly good time had by all!

‘till the next time Keith

Registered Charity No. 285809